During my childhood, school was a safe haven. It was easy, and I knew exactly what to do to succeed. No surprise then that at 21, I became a teacher myself. What was a surprise, and remains one, is that my son – a child with half my genes, who grew up being doted on by all my students and colleagues- hates school.

During my childhood, school was a safe haven. It was easy, and I knew exactly what to do to succeed. No surprise then that at 21, I became a teacher myself. What was a surprise, and remains one, is that my son – a child with half my genes, who grew up being doted on by all my students and colleagues- hates school.

This isn’t a recent 3rd-grade revelation either; it started in Pre-K. We lived in Washington Heights when he was a toddler, and all signs pointed to him being gifted. My mom watched him and a friend’s child, teaching them things like colors and shapes at an early age. He had a vocabulary of over 20 words before his first birthday. Honestly, I could go on with all the examples of him being bright beyond measure. But, soon enough, it was time for school.

As a New York transplant with very few mom friends, I had no idea how the Pre-K lottery worked. I thought I was lucky when we were assigned to a community center less than ten blocks away. Upon further research via the moms’ groups on FaceBook, I realized I should have been planning and lobbying for a spot at a top-rated school for years. So, when things started to not go well in Pre-K (you know, texts from his teachers about behavior and reports of him not sleeping during nap time), I thought it was my fault. We worked triple time at home to make up for it: reading books about school, playing “classroom,” and planning for the following year.

Then came Kindergarten. When he came home, I’d ask about the day. He couldn’t remember much and didn’t want to talk about it. I asked teachers for more frequent check-ins, and they wrote home about his behavior, dropping words like “unfocused” and “impulsive.” I thought that they were overreacting, and he was being a boy. I asked my mom to volunteer as a classroom parent to keep an eye on things. She thought maybe having so many kids in the class was the issue. There were a lot of distractions and not enough individualized attention. After all, he was used to being the center of it all, and at school, he wasn’t.

That was a significant factor in the decision for us to move to Westchester. I wanted smaller class sizes, more of a community school feel, and a fresh start for my son.

That summer, I spent most of my time researching schools and then looking for apartments within close proximity. I found a Montessori school I loved and picked an apartment less than a block away. Then, I registered my son for school and found out we could not enter him into a Montessori school because he didn’t go to Montessori Kindergarten or Pre-K. We were, instead, assigned to a school a half-mile away.

It was everything I didn’t want: big, not diverse, and test-focused.

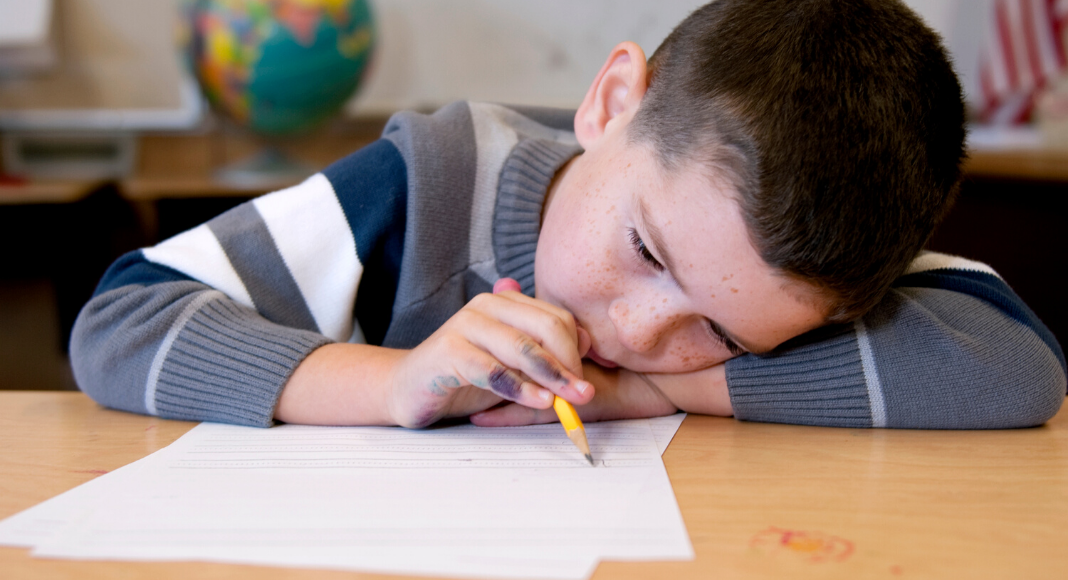

Things went from bad to worse. He would wake up complaining of being sick and not wanting to go. He was often denied recess for his “bad” behavior. He had to sit by himself, not at a table with other students because he was a distraction. Teachers developed new words for him: defiant, incorrigible, and not willing to learn. I knew all of this was untrue. My son was a great learner. He loved going to the “bones museum” and memorizing new dinosaur names, his favorite TV show was Wild Kratts, and we never missed bedtime books.

There was something about school, though, that made him feel bad.

School for me was a welcome respite from home. I escaped into the library and found a book to read quietly in the soft embrace of our whistle chairs. My son and I were very different people, though. He loved being outside and exploring; being quiet was a foreign concept to him. I thought deeply about the ways our school system embraced the archetypal feminine qualities of silence and stillness. It was a difficult realization that the profession I loved rejected the things I loved about my son.

This made me think about my own classroom. How many times a day did I ask my students to be at a level zero or to lower their voices? How many hours did they have to spend in their seats? Then, the most challenging question of all, how many of my students hated school?

I hope none of them wake up begging to stay home – although I’m sure at some time over the last twelve years they have. Now I actively work to make sure my classroom is where all students can feel comfortable and successful.